The “Problem” of Masculinity

The Five Stages of Masculinity is a tool intended to map out the various stages of masculinity that many people experience. Everyone experiences masculinity to some degree, either as a man (and some women) who internally embodies masculinity, or as a woman (and some men) who is externally impacted by masculinity.

The Five Stages works from the assumption that masculinity is a “problem” that needs to be solved. The reasons for this are twofold, and how much you relate to these two reasons will depend on your worldview of gender politics:

- Masculinity is a problem because it results in negative experiences for men in domains such as physical and mental health, education, homelessness, violence, and incarceration.

- Masculinity is a problem because it results in negative experiences for women and atypical men in the form of patriarchy, and for society in general in most domains due to assertions of power and domination.

People who resonate most with the first point are likely to align themselves with men’s rights advocates. People who resonate most with the second point are likely to align themselves with feminists. Both groups can be simultaneously correct, and their success in arguing their point does not have to rely on disproving the other.

Between the individual experiences of men outlined in the first group and the systemic experiences of women (and society in general) outlined in the second group, masculinity causes a lot problems. Indeed, after the environment, masculinity arguably causes the most problems for our civilization (further still, part of why the environment is in a mess is also down to masculinity). A detailed exploration of these problems can be read in the free eBook, The Masculinity Conspiracy.

A key assumption of The Five Stages is that masculinity is not a fixed thing. We can see that what is meant by masculinity shifts depending on when and where you are: For example, regular masculinity looks very different in South Korea than it does in South Dakota. If masculinity is the cause of numerous problems, and if masculinity is changeable, we should be able to first think and then act our way towards solutions to these problems.

The Stages

The Five Stages starts with the most populous and most problematic manifestations of masculinity and works its way up. As we rise through the stages, three things happen:

- each stage is inhabited by a decreasing number of people

- each stage has characteristics that become increasingly complex and more nuanced

- each stage reveals more methods for identifying and mitigating the problem of masculinity

By mapping where people are in regard to their understanding of masculinity, The Five Stages functions as a catalyst to propel people towards the next stage, which in turn will increase the likelihood of solving the problem of masculinity. Most people will need to explore each stage in full before they can leave it behind. However, some people are lucky enough to have resisted social conditioning around masculinity and have always inhabited a later stage. Structurally, The Five Stages shares some commonality with other developmental models such as the ethnic identity stages articulated by William E. Cross; however The Five Stages does not seek to apply any specific existing model.

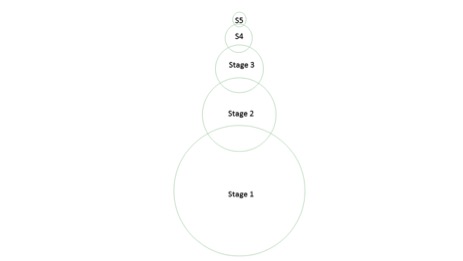

But let’s get one thing straight from the start. These are not the stages of masculinity but, rather, some stages of masculinity. Moreover, the stages are porous and overlapping. When visualizing the stages it is tempting to imagine a triangle akin to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The overall direction of this is sound, but it is too crude. A more useful way of visualizing the stages is a pyramid-shaped Venn diagram, with different-sized circles indicating numbers of inhabitants and clear points of overlap. In reality, the stages are more numerous, their characteristics more multifaceted, and their relation less linear. But for the sake of simplicity, the Venn pyramid will serve the purpose.

The Five Stages of Masculinity Venn Pyramid

Stage 1: Unconscious Masculinity

Stage 1 is defined as “unconscious masculinity,” which means that the standard social construction of masculinity has been adopted by someone without them even thinking about it. More people inhabit Stage 1 than any other stage.

Unconscious masculinity is the most problematic of the stages for various reasons:

- the standard and problematic social construction of masculinity is understood by people as intuitive, common sense, and “natural”

- the problem of masculinity is therefore acted out by people without any awareness, preventing the identification of the problem, let alone a solution

- the problem of masculinity is passed on unconsciously, thus perpetuating unconscious masculinity from generation to generation

- the very act of enabling someone to realize they have been subject to unconscious masculinity can be very difficult, making moving on from even this first stage perhaps more elusive than any other stage

If you’re reading this article you have probably already moved on from Stage 1.

Stage 2: Conscious Masculinity

Stage 2 is defined as “conscious masculinity” and has perhaps the most numerous permutations of all the stages. The common thread running through these different permutations is the awareness that there is a level of regulation that takes place around contemporary masculinity. The understanding of that regulation shifts depending on which form of conscious masculinity is embodied.

Some of the key forms of conscious masculinity include:

- Naturalists, who are similar to people at Stage 1 inasmuch as they perceive masculinity as intuitive, common sense, and “natural.” However, this is a conclusion drawn from contemplation rather than the blind embodiment of unconscious masculinity. Naturalists often believe masculinity is being denied and neutered by modern society.

- Men’s rights advocates, who identify certain problems with masculinity (such as physical and mental health, education, homelessness, violence, and incarceration) and perceive these to be ignored. Men’s rights advocates often believe masculinity is being attacked by feminists.

- Spiritualists, who are similar to Naturalists inasmuch as believing in an authentic masculinity that should be recovered. They believe models for masculinity can be found in holy texts or more general spiritual principles. Spiritualists often believe masculinity is being denied by a society that has lost its spiritual way.

- Agnostics, who are a more general category of people who share certain beliefs with the above forms of conscious masculinity, but not all. Agnostics generally believe there is a problem with masculinity, but struggle to fully articulate the nature of that problem, let alone a solution.

Stage 2 has the potential to overlap with Stage 1. For example, a men’s rights advocate may have a conscious and detailed analytical framework explaining some social aspects of masculinity (such as health) yet operate unconsciously in regard to other aspects (such as fatherhood). Stage overlaps should not necessarily be considered in a negative light. Areas of overlap are potentially the most fruitful in terms of personal change and movement up the stages. Areas of overlap also muddy the waters as to which “camp” a person belongs to: the blurring of these boundaries and the new alliances that can be made as a result are also fruitful.

Stage 3: Critical Masculinities

Stage 3 is defined as “critical masculinities” and is largely aligned with feminist thought. Given there are various forms of feminist thinking, there are also various forms of critical masculinities. Some key commonalities that can be found among critical masculinities are:

- society operates via patriarchy, which oppresses women

- society operates via hegemony, which oppresses atypical men (such as gay men and straight men who resist patriarchy)

- masculinity is not natural, rather socially-constructed

- masculinity is not singular, rather plural masculinities (in other words, changeable)

Critical masculinities opens up a sophisticated level of analysis by doing justice to the nature of systemic power. Indeed, the reason why Stage 2 and Stage 3 often appear in conflict is because Stage 2 privileges individual experience whereas Stage 3 privileges systemic experience. A good deal of this conflict could be de-escalated if both stages realized they are often speaking at cross-purposes.

However, Stage 3 has certain blind spots. Despite the acknowledgement of plural masculinities, Stage 3, like various streams of feminist thought, suffers from essentialism. Thinking systemically does not always do justice to the subtlety of individual experience. Furthermore, the category of “man” and “woman”—so fundamental to feminist thought—assumes a commonality within those categories that can be hard to justify. Indeed, in Stage 3 those categories of “man” and “woman” can look suspiciously like Stage 2 Naturalists, and may even dip back into the unconsciousness of Stage 1.

Stage 4: Multiple Masculinities

Stage 4 is defined as “multiple masculinities” and is largely aligned with queer theory. Queer theory was born out of the experiences of gay and lesbian people, but its implications are much broader. In short, queer theory is based on three fundamentals:

- masculinity can mean anything to anyone (including being embodied by women)

- masculinity is defined and categorized through power dynamics such as patriarchy and hegemony as a way of regulating people

- by rejecting categorization we subvert regulation and power

The implications of queer theory are profound. No longer is there masculinity and femininity (or even, really, men and women). Instead, each individual dwells in a category of sex and gender as unique as their fingerprint. Stage 4 is ultimately about freedom: the freedom to be who you want, and the freedom to let others be who they want.

There are a couple of drawbacks to queer theory:

- it is difficult for people who are not “gay” to fully get behind it

- there are some logical problems with the thinking around queer theory; for example, it is inconsistent to work against the regulatory function of gender and sexuality categorization, yet routinely describe people as “straight” or “cis,” when this serves little purpose other than to place people in a category based on their gender and sexuality

Stage 4 also leaves us with a lingering question: If masculinity can mean anything you want it to mean, does it have any meaning at all?

Stage 5: Beyond Masculinities

Stage 5 is defined as “beyond masculinities” and begins to tackle the crisis of meaning opened up by Stage 4. Very few people consciously operate at Stage 5, although a larger number of people probably intuit its presence.

The bottom line of Stage 5 is the simple truth that masculinity does not exist. However, it is difficult to connect the dots for those at earlier stages and move them towards solutions to the problem of masculinity when one has to eventually concede that masculinity is not real (in which case, how can it cause a problem!). Of course, it is the reification of standard masculinity that is the problem. In other words, standard masculinity exists as a consensual hallucination which nevertheless has many real effects.

Even so, the Stage 5 mind still wants to bring form to the concept of masculinity, as its eventual non-existence seems a rather cruel existential joke. As such, here are two tools that can be employed that might be used to fashion some kind of form, acknowledging that we are teetering on the very edge of language: the first tool conceptual, the second methodological.

First, psychoanalysis offers the concept of “individuation,” which is a process where individual consciousness is brought into being. “Pre-individuation” can be seen as the primordial state before personal identity—and with it, masculinity—is established. Locating masculinity in the space of pre-individuation would suggest some kind of reversion to the womb, but “post-individuation” could be a space that resists the identity bestowed by individuated masculinity while remaining conscious of its nature. A spiritual form of this comes in the Eastern concept of Ātman, which represents one’s eternal soul or essence. In this context, masculinity is but one of many illusions from which we must be liberated before experiencing transcendence.

Second, the medieval Christian mystics had a method of speaking about God called the “via negativa,” which seeks to describe God not by what S/he is but by what S/he is not. This process aspires to bring form to the experience of God while accepting that S/he is ultimately beyond human perception. The via negativa could similarly be used to think around masculinity: if not to say what it is, then at least to answer attempts to contain and regulate it.

People who are not sympathetic to a spiritual worldview may turn off at this point, but this is not some covert attempt to evangelize. These tools work just as well for atheists as spiritual people. It just so happens that religion has an extensive history of articulating the beyond. In the end, Stage 5 is not a stage, rather a signpost to somewhere else that—without sounding too grandiose—humanity has yet to explore.

A Final Note

This is The Five Stages of Masculinity, not The Five Stages of Gender or The Five Stages of Femininity. All three of these Five Stages start in the same broad mess of Stage 1 and end in the same focal point of Stage 5, however the dynamics of the in-between stages may be different.

Find out which stage you are at by using our the tool:

The Five Stages of Masculinity Personality Inventory

Dr. Joseph Gelfer is the author of Masculinities in a Global Era (Springer Science+Business Media, 2014) and Numen, Old Men: Contemporary Masculine Spiritualities and the Problem of Patriarchy (Routledge, 2009). He has has also written the free eBook The Masculinity Conspiracy (600kb pdf) and the Future Masculinity online course on the Udemy learning platform.